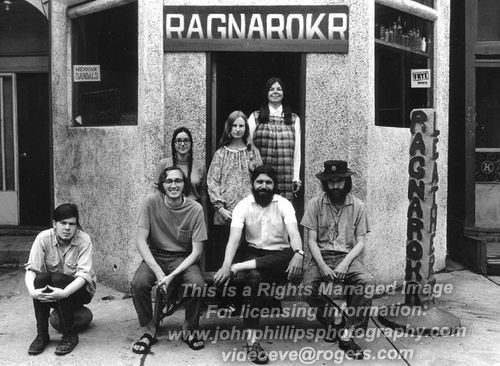

I really was just looking for any photos of Ragnarokr (the store at 33 Baldwin St. that I remember so well, not the later incarnation, see here) to add somehow as an image on my “About” (or should it be Aboot?) page, and stumbled on this book....

Robert Fulford's column about Vietnam war resisters in Canada:

John Hagan, a sociologist who has become an expert on draft dodgers, thinks that about half of the 50,000 Americans who came to Canada in the Vietnam-war era have, like him, remained here. But whatever happened to them? After three decades, where have all the dodgers gone?

....

It was a vivid, eventful period, and

Northern Passage (available at Amazon) captures it deftly. John Hagan, now 55 and attached to the University of Toronto law school, has written on subjects such as the lives of lawyers, relations between the law and the Chinese in Canada, sentencing procedures and homelessness. At the moment he's studying the procedures of the war-crimes tribunal at The Hague. Last week he and I had lunch at a window table at Cafe la Gaffe, one of the 22 restaurants that today fill Baldwin Street, the little block south of the University of Toronto where dodgers roosted in the early 1970s.

We surveyed the Indonesian and Chinese restaurants across the street and tried to figure out precisely where the dodgers' famous photography gallery (long dead) was located -- was it next to the crafts store (also long dead), or farther along? This story has engaged Hagan for many years. He decided when he first arrived in Canada that he would someday tell it, and in the 1990s he conducted sociological interviews with the war resisters. He spent two arduous years in the editing process with Harvard University Press, because he wanted an account of these people (who are mostly forgotten in the U.S. as well as Canada) to have a place on the top rung of American academic publishing.

The Toronto dodgers found their geographical focus, by a process no one remembers, on a downtrodden street that was mostly abandoned by the old Jewish community and not yet taken up by the Chinese. Dozens of dodgers settled around Baldwin, then scores, then a few hundred. Many newcomers went there to find their feet and quickly moved on. Over five years, one house contained roughly 100 different dodgers for brief periods. Baldwin Street acquired co-operative craft stores (the Yellow Ford Truck and Ragnarokr), a cheap clothing store (the Cosmic Egg), the Whole Earth Natural Foods Store, and the Baldwin Street Gallery, a pioneering photography centre. One of the gallery's owners, John Phillips, turned out to be an especially enthusiastic new Canadian. Many years later he recalled the day he drove into Canada as a moment of ecstasy, one of the happiest times of his life.

Baldwin Street developed a communal atmosphere, what one deserter (originally from Vermont) later recalled as a small-town feeling. It was a place where people knew their neighbours and enjoyed the consolations of familiarity and acceptance. It was a community built around a political issue, however, and the issue was resolved when the Carter administration forgave the dodgers and invited them home. The Baldwin Street ghetto lost its reason for being, and before the 1970s were over it vanished. Some of the people who had needed it were by then back home, being Americans again, and many of the others had turned into Canadians.

I remember the Yellow Ford Truck (a door or two down), but don't really remember going inside often. The Cosmic Egg I vaguely remember as being about half a block away, but the Whole Earth Natural Foods still evokes smell memories, including a big vat of freshly ground peanut (or other nut) butter. John Philips I recall as well, and his son Morgan was one of my playmates for a time.

Amazon has the index to the book, and I see Steven Burdick, Philip Mullins, Janice Spellerberg listed. Maybe I'm spelling Ragnarokr incorrectly too, doh!

and a fairly nit-picking article about Hagan's book, here

Hagan’s research is based mainly on one hundred interviews from a sample population, archival materials with related interviewing, and census data. This body of primary source material ensures that his work will have ongoing interest. Thirty of the one hundred interviewees were women. To his credit, Hagan has gone further than any other researcher in elaborating their role, both as individuals and as a definable group.

Of the previous monographs on the subject, only Renée Kasinsky’s Refugees from Militarism: Draft-Age Americans in Canada (1976) receives more than a passing mention. No account is taken of relevant theses, notably Sharon Rudy Plaxton’s 1995 Queen’s Ph.D. on the Ford and Carter amnesties and Patricia Mackie’s 1998 Concordia M.A. on socio-political aspects of Canadian immigration policy. The nature of the interview sample raises questions about representativeness. The focus is Toronto only, and the most productive chain of referral starts from a major activist. Despite substantial attention given this matter, a conclusion that the sample is “not atypical” remains unconvincing.

Distinct topics and source material make up the six chapters. What unity there is derives from thematic continuities, a broad chronological progression, and the interview form. Regarded as history, the book offers outstanding accounts of shifting Canadian government immigration policy and the exile-led campaign for amnesty.

Other treatments of history need to be approached with caution. The story of Mark Satin and the establishment of the Toronto Anti-Draft Programme derives mainly from a few biased sources. The chapter on Toronto’s American ghetto relies heavily on one oral history collection, focuses on Baldwin Street hippie enterprise, and neglects organizations like Red, White, and Black, the Hall, and Black Refugee Organization (BRO). A distinctive statistical profile for 1970 immigrants leads to a repeated and too-simple correlation with the War Measures Act. Presenting the Canadian government’s 1973 Adjustment of Status Program as an “amnesty” proves more confusing than helpful.

One comment in the closing chapter “Choosing Canada” reveals that almost a quarter of the sample “lived for a time in the United States since originally coming to Canada,” and some undefined portion even now lives in the United States. In a recent journal article Hagan has highlighted aspects of resister ambivalence and provided data not found in the book. Contradictory tendencies deserve more explicit analysis, even though exposition has given them voice.

Phil has the book. He says that it's, for the most part, right on.

I have a copy of that book sent to me by Janice Spellerberg about two years ago. I told George I will loan it to him. The book is a study of how the draft dodgers adopted to their status in Canada. He spends an entire chapter (one chapter out of six in the book) on the Baldwin Street community, mentioning all the people you listed. He does a great job in this chapter with few errors. What surprised me was the importance he attached to the Baldwin Street experience. He inspires me to continue work on the history of Ragnarokr which I started some time ago. I set the project aside to revise the family history book but that is finished now and so I have no excuses. I think that the Ragnarokr was a major part of the Baldwin Street scene and so maybe there will be some interest it a history that focuses on the leather shop and its role in the Toronto exile community.

I was a US Army deserter during the Viet Nam who lived in Vancouver and in Toronto. I remember the Cosmic Egg but not the others. I spent most of my time living in Rochdale College (15th floor commune), so that was the center of my life then, and my memory of the Baldwin Street area is vague. But that was a great and exciting time, and frankly I wish we could have again the hope, the dream, the aliveness again, without the pain, the war, oppression from the system, etc.

I'm now back in the States working to end this new war and working with current day war resisters and vets. The times are very dark here in the US, but I still hope that the dream can come again. And I still work and fight for that dream. Hello to all my brothers and sisters who also are still in the fight. Thank you all.

Dear Seth,

I think I remember you as a child. Is your mother's name Colleen and did she live at the Yellow Ford Truck commune in Toronto and later with George Mullins at the Ragnarokr leather commune on Baldwin?

I was connected to the Whole Earth Store and you and your mother spent a little time with us in 72 I think. If I'm correct, you then left for California with your mom and George. George was driving the front part of a huge truck with no trailer connected to it. Your mom was a beautiful girl with long dark culy hair I think.

Do I have it right? You were an adorable toddler with sandy blonde hair and seemed so old compared to our babies at the comme who were all born in 71. Your mom was very young though. Younger than us, as I remember.