Yes, I know I've blathered about being a music snob already this year, but couldn't let an article about one of my musical heroes pass without at least mentioning it.

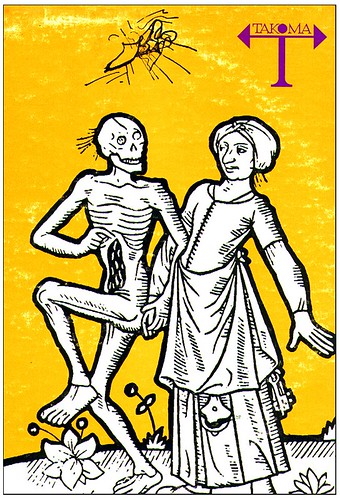

Dance of Death album cover, scanned, ink stain-doodle and all.

The Rock Snob*s dictionary omitted mention of John Fahey for some reason. I debated throwing the book at the wall, but since David Kamp and Steven Daly do say nice things about the Flaming Lips and the Small Faces, I reconsidered.

Anyway, John Fahey should be worshiped as a god - even if you don't like his mix of dissonance, distemper and melody - because he created his own Indie record label, one of the very first, so he could record what he wanted to record without kowtowing to the musical tastes of the moment.

“How Bluegrass Music Destroyed My Life” (a memoir by John Fahey)

“The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death” (John Fahey)

village voice - John Fahey by Andy Beta ...Coming to prominence in the early '60s, at the dawn of folk's re-emergence and the rise of the hippie counterculture, John Fahey revolutionized steel-string guitar playing by wedding the fingerpicked blues of Mississippi John Hurt to the structuring prin-ciples of classical composers like Sibelius and Brahms to craft something wholly American. Or as a 1959 article (included in the recent Fonotone box set) noted: “[Fahey] never fully grasped the meaning of Heidegger's angst until he heard it expressed in its supreme articulation on a 78 rpm record by Blind Willie Johnson.” Ignoring the segregation of high and low culture, Fahey found something endemic to both, creating a body of work that hangs in the halls of American genius somewhere between Coltrane and Whitman.Fahey passed from this world some five years ago during a septuple bypass, so it's funny now that these nascent recordings he made as Blind Thomas for Fonotone, the 78 rpm label of collector Joe Bussard (think Steve Buscemi's Ghost World character times a thousand), have come back to light alongside Vanguard's release of I Am the Resurrection. A tribute album featuring indie luminaries (Sufjan Stevens, Devendra Banhart, M. Ward) pays reverent homage to the man. And why not? Fahey, aside from his astounding music, set an example with one of the earliest independent, artist-run record labels, Takoma. He released the debut albums of Leo Kottke and George Winston. Fahey also rediscovered Skip James, the malevolent Depression-era master, traversing a brutally segregated Mississippi to find him in a hospital bed; it strangely presaged Fahey's own rediscovery in a Salem, Oregon, men's center in 1994 by Spin's Byron Coley.

Soused and spiteful at shows, misunderstood by an audience wanting peace, love, and his old songs, Fahey loathed both his hippie followers and his imitators. Will Ackerman and the whole New Age neutering of Fahey's guitar style that cropped up in his wake were anathema to him; his true progeny were the tetchy alternative noisemakers, like Sonic Youth and Wilco. The tribute [album?] makes this clear, recasting his iconoclastic solo pieces with winsome arrangements from its participants. And yet reverence to the song was never his own agenda, as Fahey often disavowed his past discography outright.

“I Am the Resurrection: A Tribute to John Fahey” (Various Artists)

more from Andy Beta of the Village Voice

When not canvassing for classical records, we'd be back in his motel room. My awe quickly turned to mild mortification at Fahey's ability to ingest anything and everything: a block of cheddar cheese unwrapped and munched like a candy bar; cold, greasy okra from the previous night; a squished french fry on the bed, suddenly remembered and swallowed. Amid the detritus of crumpled yen and girls' addresses in Osaka, finger paintings rendered on photo album sheets, New Age CDs called Music for Brain Waves, we auditioned the early master tapes of volume four of the Harry Smith collection. Fahey mused about how it reflected the Depression despite the set's upbeat ending. He declared “Last Fair Deal Gone Down” the best Robert Johnson song, and said the Carter Family sounded like they were dead, a zombie chorus. He would sprawl across his bed, enrapt in the ancient sounds, his giant white belly puffed out. Slowly, a guttural moan would be loosed from his depths, a half-drone, half-growl that drowned out the tape.Other times, he would play his mixes: collages of Nazi rallies, Balinese gamelan, and recent Chicago blues licks with their verses and choruses mischievously lopped off, rearranging their 12- bar logic. Whether it was blue plate specials, convenience store crap, or world music, all went into his maw. Such devouring and consumption was what Fahey did throughout his career. His repertoire mashed Hammerstein with Dvorak, Christian hymns as well as Hindi chants, Dock Boggs and Duke Ellington. Classic albums like Requia and Days Have Gone By feature the same sort of aural collages he was still spinning 30 years on, as if no time had elapsed. Dislocation isn't too odd of a sensation, as critic Nat Hentoff recognized: “[Fahey's] music keeps stirring up old memories and all kinds of new anticipations.”

“Legend of Blind Joe Death” (John Fahey)

“Georgia Stomps, Atlanta Struts, And Other Contemporary Dance Favorites” (John Fahey)

Tags: John_Fahey, /LSD, /music