I renew my public request for some wealthy liberal, George Soros, Richard Branson, perhaps even Ronald W. Burkle (of Yucaipa Companies) to purchase Diebold, and change the company's penchant for secrecy into one of open source, with transparent security measures. Why should Diebold be allowed to hide behind phony intellectual property shields: we, the citizenry, are all participants in voting, we should all have oversight over the process and mechanics of voting. How about Bill Clinton, Al Gore, CC Goldwater and Robert Kennedy lead a consortium of bi-partisan investors to take over Diebold? Something obviously needs to be done.

Officials Wary of Electronic Voting Machines

Officials are making last-minute efforts to limit or reverse the rollout of new machines in the November elections.

...

But critics say bugs and hackers could corrupt the machines.

A Princeton University study released this month on one of Diebold’s machines — a model that Diebold says it no longer uses — found that hackers could easily tamper with electronic voting machines by installing a virus to disable the machines and change the vote totals.

Mr. Radke dismissed the concerns about hackers and bugs as most often based on unrealistic scenarios.

“We don’t leave these machines sitting on a street corner,” he said. “But in one of these cases, they gave the hackers complete and unfettered access to the machines.”

Warren Stewart, legislative director for VoteTrustUSA, an advocacy group that has criticized electronic voting, said that after poll workers are trained to use the machines in the days before an election, many counties send the machines home with the workers. “That seems like pretty unfettered access to me,” Mr. Stewart said.

and from the same edition of the NYT:

Digital Domain: The Big Gamble on Electronic Voting

Diebold declines to let Princeton researchers test the latest voting machine, which uses a standard industrial part to protect the door to its memory card slot.

Edward W. Felten, a professor of computer science at Princeton, and his student collaborators conducted a demonstration with an AccuVote TS and noticed that the key to the machine’s memory card slot appeared to be similar to one that a staff member had at home.

When he brought the key into the office and tried it, the door protecting the AccuVote’s memory card slot swung open obligingly. Upon examination, the key turned out to be a standard industrial part used in simple locks for office furniture, computer cases, jukeboxes — and hotel minibars.

Once the memory card slot was accessible, how difficult would it be to introduce malicious software that could manipulate vote tallies? That is one of the questions that Professor Felten and two of his students, Ariel J. Feldman and J. Alex Haldeman, have been investigating. In the face of Diebold’s refusal to let scientists test the AccuVote, the Princeton team got its hands on a machine only with the help of a third party.

Even before the researchers had made the serendipitous discovery about the minibar key, they had released a devastating critique of the AccuVote’s security. For computer scientists, they supplied a technical paper; for the general public, they prepared an accompanying video. Their short answer to the question of the practicality of vote theft with the AccuVote: easily accomplished.

The researchers demonstrated the machine’s vulnerability to an attack by means of code that can be introduced with a memory card. The program they devised does not tamper with the voting process. The machine records each vote as it should, and makes a backup copy, too.

Every 15 seconds or so, however, the rogue program checks the internal vote tallies, then adds and subtracts votes, as needed, to reach programmed targets; it also makes identical changes in the backup file. The alterations cannot be detected later because the total number of votes perfectly matches the total number of voters. At the end of the election day, the rogue program erases itself, leaving no trace.

On Sept. 13, when Princeton’s Center for Information Technology Policy posted its findings, Diebold issued a press release that shrugged off the demonstration and analysis.

...

I spoke last week with Professor Felten, who said he could not imagine how a newer version of the AccuVote’s software could protect itself against this kind of attack. But he also said he would welcome the opportunity to test it. I called Diebold to see if it would lend Princeton a machine.

Mark G. Radke, director for marketing at Diebold, said that the AccuVote machines were certified by state election officials and that no academic researcher would be permitted to test an AccuVote supplied by the company. “This is analogous to launching a nuclear missile,” he said enigmatically, adding that Diebold had to restrict “access to the buttons.”

I persisted. Suppose, I asked, that a test machine were placed in the custodial care of the United States Election Assistance Commission, a government agency. Mr. Radke demurred again, saying the company’s critics were so focused on software that they “have no appreciation of physical security” that protects the machines from intrusion.

and far from making me feel more secure about my rights as a citizen, Diebold wants to squelch any debate about their methods and practices.

Computer scientists with expertise in security issues have been sounding alarms for years. David L. Dill at Stanford and Douglas W. Jones at the University of Iowa were among the first to alert the public to potential problems. But the possibility of vote theft by electronic means remained nothing more than a hypothesis — until the summer of 2003, when the code for the AccuVote’s operating system was discovered on a Diebold server that was publicly accessible.

The code quickly made its way into researchers’ hands. Suspected vulnerabilities were confirmed, and never-contemplated sloppiness was added to the list of concerns. At a computer security conference, the AccuVote’s anatomy was analyzed closely by a team: Aviel D. Rubin, a computer science professor at Johns Hopkins; two junior associates, Tadayoshi Kohno and Adam Stubblefield; and Dan S. Wallach, an associate professor in computer science at Rice. They described how the AccuVote software design rendered the machine vulnerable to manipulation by smart cards. They found that the standard protections to prevent alteration of the internal code were missing; they characterized the system as “far below even the most minimal security standards.”

Professor Rubin has just published a nontechnical memoir

Brave New Ballot: The Battle to Safeguard Democracy in the Age of Electronic Voting

(Morgan Road Books), that describes how his quiet life was upended after he and his colleagues published their paper. He recalls in his book that Diebold’s lawyers sent each of the paper’s authors a letter threatening the possibility of legal action, warning them to “exercise caution” in interviews with the press lest they make a statement that would “appear designed to improperly impair and impede Diebold’s existing and future business.” Johns Hopkins rallied to his side, however, and the university’s president, William R. Brody, commended him for being on the case.

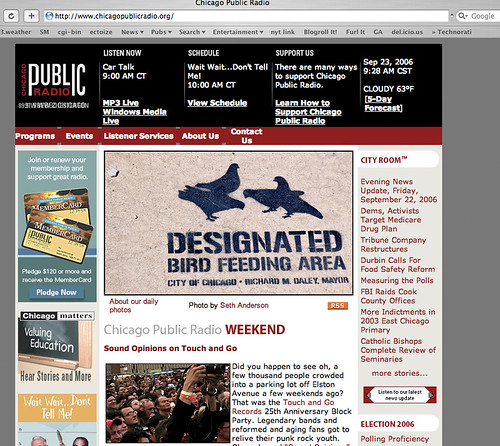

More on the subject here

Diebold Whistle-blower speaks out

Vote Flipping in GA

link to Princeton study, and 'how-to' video.

Tags: Al_Gore, /Clinton, /Diebold, /election, /electronics

![Exile On Main Street [Limited Edition]](http://images.amazon.com/images/P/B00001R3GI.01._SCMZZZZZZZ_.jpg)

First, the bad news: I’m fired. MSNBC.com has decided to end its support of “Altercation,” and indeed, all of its association with yours truly as of this Friday.Ok, now, the good news: My friends at Media Matters for America have decided that the cause of continuing “Altercation” in its current, politically independent form to be worthy of their support. So we’re not dying, just moving. Our new URL will be

First, the bad news: I’m fired. MSNBC.com has decided to end its support of “Altercation,” and indeed, all of its association with yours truly as of this Friday.Ok, now, the good news: My friends at Media Matters for America have decided that the cause of continuing “Altercation” in its current, politically independent form to be worthy of their support. So we’re not dying, just moving. Our new URL will be